Struggling to work out the best settings for your podcast’s technical production? Ever wondered exactly what the top podcasters are doing and how they compare to each other? Wonder no more!

As a little exercise I thought it might be interesting to look at a few of the top podcasts about podcasting to see what their final production quality is like and how they compare to each other.

This following analysis is purely based on the quantifiable aspects of the “final product” of the podcasts and as such aims to be entirely objective. No consideration is given to the actual content of the podcasts, or indeed whether the hosts can actually string together a coherent sentence or not (as it happens they all seem to do remarkably well on this account).

While I’ve tried to be as accurate and methodical in my approach as possible I do not make any claims about its scientific rigour, but hopefully I’ve remained neutral and have explained all of my methods and reasons along the way.

The Top Four Podcasts about Podcasting

For this exercise I chose four podcasts about podcasting that I regularly listen to and the ones I believe are evangelizing podcasting and are, or should be, at the top of their game. They are, in alphabetical order so as to show no bias:

- Podcast Answer Man [PAM] – Cliff J. Ravenscraft

- School of Podcasting [SOP] – David Jackson

- The Audacity to Podcast [TAP] – Daniel J. Lewis

- The Podcasters’ Studio [TPS] – Ray Ortega

Podcast File Format and Embedded Information

Before analysing the audio of the individual podcasts we’ll first look at the podcast files themselves, their formats and any meta data contained therein. The tools used for this analysis were MediaInfo and Mp3tag.

| PAM | SOP | TAP | TPS | |

| Ref. Episode | #351 | #402 | #167 | #082 |

| File Type | MP3 | MP3 | MP3 | MP3 |

| Codec | MPEG 1 Layer III |

MPEG 1 Layer III | MPEG 1 Layer III |

MPEG 1 Layer III |

| Bit Rate | 128 kbps | 64 kbps | 64 kbps | 128 kbps |

| Bit Rate Type | Constant | Constant | Constant | Constant |

| Sample Rate | 44.1 kHz | 44.1 kHz | 44.1 kHz | 44.1 kHz |

| Duration | 1:01:32 | 1:08:59 | 0:36:59 | 1:01:52 |

| File Size | 56.7 MB | 31.6 MB | 17.0 MB | 56.7 MB |

| Mono/Stereo | Joint Stereo (MS) | Mono | Mono | Joint Stereo (MS) |

| Filename | PAM351-SharkTankb.mp3 | sop402_ 033114.mp3 |

tap167.mp3 | TPS082_ _Zoom_H6_and_ Crowdfunding_for_ Podcasters.mp3 |

| ID3 Genre | Podcast | Podcast | Technology | Podcast |

| ID3 Year | – | 2014 | 2014 | 2014 |

| ID3 Track | – | 402 | 167 | – |

| ID3 Album | PodcastAnswerMan.com | The Morning Announcements | The Audacity to Podcast | The Podcasters’ Studio |

| ID3 Artist | Cliff Ravenscraft | David Jackson | Daniel J. Lewis | Noodle.mx Network | Ray Ortega |

| ID3 Title | On Air Signs – Shark Tank Podcast – And So Much More | Jordan Harbinger Left His Law Career to Do Podcasting Full Time | What is RSS? And why you MUST own yours – TAP167 | TPS082: Zoom H6 and Crowdfunding for Podcasters |

| ID3 Comments | – | 518 chars | 533 chars | 98 chars |

| ID3 Image Size | 541 kB JPEG 1400 x 1400px Other |

35 kB JPEG 300 x 300px Front Cover |

169 kB JPEG 1400 x 1400px Other |

95 kB JPEG 600 x 600px Other |

| Other ID3 Tags | – | – | COPYRIGHT, ENCODEDBY, PODCAST, PODCASTDESC, PODCASTID, PODCASTURL, WWW |

COMMENT ITUNNORM, COMMENT ITUNPGAP, COMMENT ITUNSMPB, ENCODEDBY, COMPOSER UNSYNCEDLYRICS |

So, what does all this tell us?

Well, despite many commonalities, even amongst the leading proponents of podcasting there are clearly differences of opinion as to what approaches to adopt. There is obviously no perfect way of doing things, but perhaps more variations on a theme.

Cliff and Ray have gone for higher bit rates and stereo files, which while undoubtedly giving higher audio quality mean file sizes are proportionally larger and take longer to download.

Cliff Ravenscraft uses the least number of descriptive ID3 tags in the MP3 files, choosing to ignore even some of the most common podcast ID3 tags such as the year and track or podcast episode number. Ray and Daniel certainly win for the most number of ID3 tags and David and Daniel excel in their large comment fields.

Podcast cover art is pretty important as this is what listeners see on their playback devices. All of the podcasts incorporate cover art, although David Jackson opted for the Front Cover album art tag instead of the “Other” tag, which technically makes most sense I think, but ultimately depends on how the plethora of MP3 players available support these tags.

Audio Analysis

Waveform View

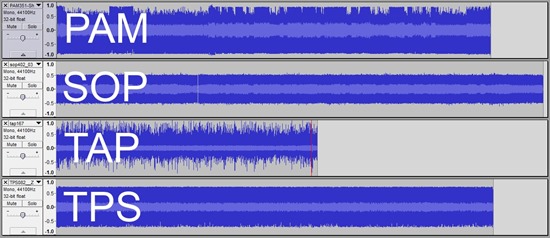

A simple waveform view of the sample audio files using the Audacity audio editor can give us a few clues about each podcast’s audio, providing useful comparisons:

In Daniels’s podcast (TAP) it’s interesting to note that his audio clipped briefly, indicated by the vertical red line. This is generally considered undesirable as it manifests itself as audible distortion.

Daniel’s audio was much more dynamic however compared to the others which were clearly heavily compressed and limited, preventing their audio levels from exceeding predetermined thresholds. We’ll discuss the dynamic range of the respective podcasts in more detail later in this article.

Frequency Response

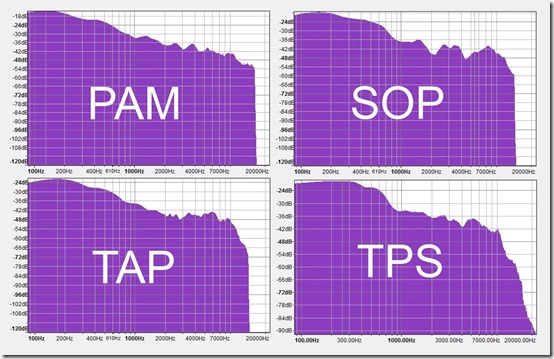

Different microphones and different voices all contribute to different frequency or spectral responses and in this respect I’m not entirely sure how much the following graphs can tell us, other then they’re pretty to look at:

Two interesting points to note though are that Cliff’s podcast has an extended low end (bass) and Ray’s podcast has a significantly extended top end (high end or treble) potentially making his podcast brighter sounding.

Dynamic Range and Loudness

Amongst the broadcast industry recent European (EBU R128) and International (ITU-R BS 1770-1) standards have been developed and adopted to measure and help control the perceived loudness levels of audio content within programmes.

These standards call for a programme loudness level of -23.0 LUFS (measured across the entire programme) with a permitted deviation of ±1.0 LU, where 1 LU is equivalent to 1 dB.

Programmes are also allowed a maximum permitted true peak level of -1.0 dBTP. True peak rather than sample peak is specified as inter-sample peaks can often exceed the maximum sample peaks, leading to digital distortion and clipping.

The following measurements were taken using the free EBU R128 and ITU-R BS 1770-1 compliant loudness analyser plugin (MLoudnessAnalyzer) from MeldaProduction used from within Cubase:

| PAM | SOP | TAP | TPS | |

| Loudness | -12.1 LUFS | -16.3 LUFS | -21.8 LUFS | -13.7 LUFS |

| True Peak | -0.37 dBTP | -3.81 dBTP | 0.01 dBTP | -1.78 dBTP |

| Peak | -0.62 dBFS | -4.43 dBFS | -0.00 dBFS | -2.42 dBFS |

| Loudness Range (LRA) | 3.4 LU | 2.4 LU | 2.8 LU | 3.2 LU |

| Peak to Loudness Ratio (PLR) | 11.73 dB | 12.19 dB | 21.81 dB | 11.92 dB |

Loudness Analysis

From the above table we can see that Cliff Ravenscraft’s podcast is the loudest and Daniel J. Lewis’ is the quietest. In fact Cliff’’s podcast is twice as loud as Daniel’s, with a 9.7 dB difference; 10 dB is usually considered as a perceptual doubling in volume.

Although the EBU R128 standard calls for a -23 LUFS loudness level in the broadcast industry, recent studies have recommended a -16 LUFS level (7 LU louder) for mobile devices due to the noisier environments in which they are likely to be listened to. In this respect, David Jackson’s podcast is pretty much spot on, Daniel’s is too quiet and the others are too loud.

Avoid Clipping

Digital distortion and clipping should be avoided at all costs and in this respect Daniel’s been a naughty boy as he exceeded 0 dBTP. Looking at the previous audio waveforms above however, it appears that Daniel only clipped at one point (the vertical red line on the right hand side of his waveform image), so perhaps he’s only been a little bit naughty.

Everyone else has avoided clipping, although Cliff is sailing a little close to the wind according to the current standards.

Dynamic Range Analysis

Dynamic Range is not the same as Loudness! A podcast can be loud, but have little dynamic range.

The loudness ranges for the podcasts measured were fairly consistent yet on the low side, which is not at all surprising considering the programme material was essentially spoken word.

The peak-to-loudness ratio (maximum true-peak compared to the average loudness level) is a more representative indication of the programme’s dynamic range measured over the short term. Looking at these figures we can see that Daniel’s podcast is by far the most dynamic as is also borne out by looking at the waveform of his podcast compared to the others.

Conclusions

What can we actually infer from the above analysis?

Well, if you can listen to the podcasts quite happily, wherever you want and on whatever equipment you have, with no problems and you enjoy them, then it means absolutely nothing at all.

If however, you’re an audio or podcast nerd, then it might be more interesting.

For myself the ID3 tags are of little importance when I’m listening to a podcast. Absolute audio perfection isn’t that important either, but I do hate audio clipping particularly as it causes my particular MP3 player to drop out momentarily at each clipping point. So for this reason I think the EBU recommendation of a maximum audio level of -1.0 dBTP is quite important.

Secondly, I hate significant variations in volume levels between podcasts and as we’ve seen from these few examples volume levels can vary tremendously.

While loudness and dynamic range are certainly not the same thing, they are linked and in the case of Daniel’s audio it would have to lose some of its dynamic range in order to increase its overall perceived loudness. Conversely though Ray and Cliff’s podcasts’ loudness could be reduced a little whilst simultaneously gaining more dynamic range.

Recommendations

- Ensure your podcasts never exceed -1.0 dBTP

- Engineer your podcasts to meet the -16 LUFS ±1 LU loudness level

- Don’t compress or limit your podcasts too much to retain dynamic range

If you’d like to read more about these new audio broadcast standards and how they relate to podcasting, then there are some excellent articles on the Auphonic blog.

For what it’s worth those are my thoughts; they may change with time as I learn more, but that’s where I am at the moment. What are your thoughts or experiences?

Amazing analysis Richard. You could probably create a whole paid service out of this;)

Appreciate you taking the time to dig into my show, the insights are definitely helpful.

Now that is an interesting thought Ray. Glad you liked the post.

I love it! Thanks for—in a way—holding us accountable.

Also, thanks for discovering my audio clip. I have things in place that should make that impossible, but something must’ve reset its settings.

Thanks Daniel, I wasn’t really trying to hold anyone accountable, I just thought it could be something interesting, albeit a bit nerdy, to do.

And there it was! I had a misplaced decimal in my hard limiter. The clipping shouldn’t happen again.

Always the simple things, but is that peak or true peak? 🙂

Excellent in depth analysis Richard. I love it and what I find interesting is that each podcaster has their very own “secret sauce” for mixing down and mastering their podcast.

Reminds me of engineers keeping the settings of radio station audio processors a tightly guarded secret 🙂

Thanks Mike and you’re very right, everyone’s audio is unique and very personal almost becoming a trademark sound.

Man, I have never been so nervous reading an article in my life! You think you’re doing things correctly, but we all get sloppy (I thought my album artwork was at least 600X600 how very 2005 of me…)

Thanks again.

Thanks Dave. You do an excellent podcast and like the others I know you take pride in what you do and are always trying to improve.

Richard, I like that, a very interesting read. I always find it hard to listen to audio that has too much Ompah in the dynamic range, and too loud is very much a turn off.

UK Radio stations have their individual brand sound. I wonder if some completely ignore the new standards from Europe. Flick between Capital in London, Absolute Radio, BBC Radio 1 and 2 and the difference is palpable. Capital seems to crank up the loudness and add compression and limiting. Radio 2 has it just right.

Creating a brand feeling through your sound is a great way to differentiate what you have to offer. A programmer who I once worked with who was also the sound guy, had the ability to make a station sound what was best described as ‘Big and Sexy’, it was like velvet in audio.

Thing is when you tuned into one of his stations you knew what it would sound like, and you knew what it was before hearing the idents.

To Podcasts though, my feeling is a Podcast voice should sound natural with added warmth without being too quiet, too loud or to too compressed – let it live.

Kevin, I couldn’t agree more. I don’t like over compressed or over processed voices and I too think BBC R2 has a nice sound. Commercial radio stations always seem to be a bit too “in your face” with the processing for my taste.

It is a tough balance for the amateur podcaster to get a decent level for listening on mobile devices without being over compressed.

Now that I understand loudness normalization a lot better, I re-read this article and found it very useful to see the problem areas in my own podcast.

I want to focus on simplicity in my workflow, so I’ll continue using a hardware compressor/limiter/gate, but change my hard limiter to -1.5 dB (since it’s just a regular peak limiter). Then I’ll ensure I’m hitting -16 LUFS.

Now to get all of my other network podcasters doing this!

Loudness normalization is not immediately intuitive, but I’m really pleased to hear that you’re on-board with the concept now Daniel, it’s going to need people like you (with your audience) to promote the concept within the community and ultimately we’ll all benefit from consistent volume levels.

I don’t blame you for wanting a simple work-flow and setting your hardware limiter at -1.5 dB is a good starting point.

Let me know how you get on and if you need any help just shout.

I just tried a rough workflow with Audition in http://CleanComedyPodcast.com/189. But I’m not happy with the results.

Things get complicated when we’re dealing with multiple tracks. 🙁

It is tricky stuff, but especially mix your multiple tracks to sound how you want them to creatively, then focus on the main stereo bus for loudness monitoring and adjust the levels accordingly.

Daniel, it’s all seems very messy but it can be quite simple. With multiple tracks, once you’ve done your processing for each as Richard mentioned, and your tracks are balanced with each other meaning one person’s audio matches the other in terms of level (you can do this by ear or meters) then hitting your target is as simple as making a gain shift. Just measure your final file with r128x or other and when it gives you your target number simply go into your edit and make the required gain shift on the master track and you’re done. So really it all just boils down to a measurement and then a gain shift.

Daniel, don’t change your settings too much. Of the four podcasts, yours is consistently the easiest on the ears, followed by Dave’s. All four sound great, but the compressed and limited FM DJ sound gets tiring on the ears after a while.

Thanks, Gary! But I have changed my loudness method so that I’m now meeting a standard -16 LUFS

I agree Daniel had/has a good sound, but aiming for the -16 LUFS loudness level still gives 15 dB of dynamic range about the average, so if everybody went for this we should have consistent volumes with a respectable dynamic range (should they wish to make use of it).